Alexander Black’s Pre-Film Picture Play

“…simply the art of the tableau vivant plus the science of photography”

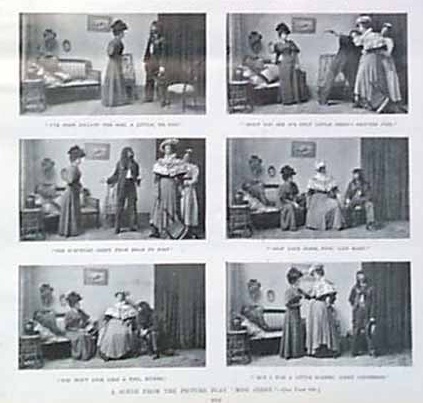

-Alexander Black, “Photography in Fiction: Miss Jerry, the First Picture Play”, Scribner’s Magazine 1895

On October 9 1894, a crowd gathered at the Carbon Studios in Manhattan for something a little different: The front of the room was draped with a screen, a magic lantern at the back of the house. The evening’s entertainment was a picture play, neither a live play nor a true motion picture, but something in the space in between. The picture play was Alexander Black’s attempt to present a play without live actors, projected on a screen with the illusion of motion created by the use of a dissolving magic lantern, accompanied by a narrated script to tell the story.

Black had been inspired by earlier magic lantern presentations he had given in front of audiences, when he noticed the natural ease with which members of the audience constructed imagined narratives to go with his photos. He created the picture play over the course of the previous summer, photographing over 200 individual stills of carefully posed motion in his studios in Manhattan, with a few images shot on location around New York City, all developed on glass plate lantern slides.

Miss Jerry told the stories of the adventures and romances of Jerry, a girl reporter in the big city, possibly inspired by Alexander’s wife, Elizabeth, who had spent her early years working in newsrooms.

The significance of the picture play was less in the technical innovation of the four-slides-per-minute motion effect, but more in the vision of presenting a full length feature in front of an audience in a permanent medium that could travel, long before Edison, the Lumiere brothers, and the other cinema creators thought to move beyond small format peep-show style contraptions and short format glimpses of motion.

Three complete picture plays were produced in all: Miss Jerry (1894), A Capital Courtship (1896) and The Girl and the Guardsman (1899). Black traveled extensively with his picture plays, presenting them to audiences around the United States.

After his death, Black’s scripts and original sets of glass slides were donated to the New York Municipal Archives, which transferred materials to the Brander Matthews collection at Columbia University in 1949. This collection was dispersed some time later, and it is unclear where some of the materials ended up. A surviving selection of slides is kept in the collections at Princeton University, and in the private collections of the Black family, but sadly, no complete picture play is known to have survived. Other papers related to Alexander Blacks’s career both as a pre-cinema innovator and as an author and editor are kept at St. Lawrence University and the New York Public Library special collections.